Technical Details of Coral Cover Statistics, and Background

By Peter Ridd – August 4, 2022

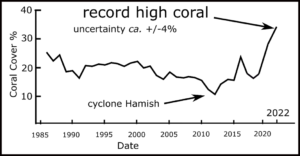

Since 1986, the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) surveys roughly 100 of the 3000 coral reefs of the Great Barrier Reef (GBR). Ridd used this data to construct the coral cover since 1986 (Figure 1) which shows that the GBR has record high coral cover.

Figure 1: Coral cover since 1986: Coral cover for 2022 is very high.

What is coral cover? Coral cover is the percentage of the seabed that is covered with coral. It is a measure of the abundance of coral. Coral cover reduces after major cyclones, when coral eating starfish numbers increase, and after some bleaching events. Coral cover at a given location usually takes five to ten years to recover from these events. Coral cover on an individual reef can drop to just a few percent after a major mortality event. It fluctuates naturally with time.

AIMS data: Raw data can be found at this link

https://www.aims.gov.au/docs/research/monitoring/reef/latest-surveys.html

The data for the GBR is broken into three regions, Northern, Central and Southern. These regions are broken into ‘sectors’ with 3, 5 and 3 sectors in the Northern, Central and Southern regions respectively. For each of the 11 sectors, there are roughly 5-10 individual coral reefs surveyed. The survey for each reef is done by towing a diver around the perimeter of each reef. The diver observes coral cover over a 140 meter distance and records the percentage estimate. Each reef is many kilometers/miles around its perimeter so there could be roughly 50 to 100 of the 140 m long sample transects for each reef.

The coral cover for each reef is an aggregate of the coral cover of all the 140-meter-long sample points. The coral cover for each sector is an aggregate for all sampled reefs in the sector. The coral cover for the major regions can be calculated by aggregating the data from the contributing sectors. The coral cover from the entre GBR can be calculated by aggregating the data from all 11 sectors (note: AIMS no longer does this last calculation).

The sector data, as found on the AIMS website, is shown in table 1 below.

| Sector | 2022

Coral cover |

| Cape Grenville | 47.0% |

| Princess Charlotte Bay | 41.0% |

| Cooktown/Lizard Is. | 25.3% |

| Cairns | 29.5% |

| Innisfail | 15.6% |

| Townsville | 34.7% |

| Cape Upstart | 30% |

| Whitsunday | 37.4% |

| Pompey | 31.8% |

| Swains | 21.8% |

| Capricorn Bunkers | 58.6% |

| Average | 33.9% |

Table 1: Coral cover for each sector of the Great Barrier Reef in 2022. Uncertainty estimates vary, but are typically between 5% and 10% according to the AIMS graphs for an individual sector.

Using these data, the coral cover for the entire reef can be calculated by averaging all the sectors, and is found to be 33.9% with an uncertainty of about 4%. This assumes equal weighting of each sector. AIMS no longer does this last calculation to get the average for the entire GBR (of 33.9%), i.e. AIMS no longer provides the final average statistic that is of most interest. It shows data for individual reefs, sector data, and region data, but not the average/aggregate for the entire GBR.

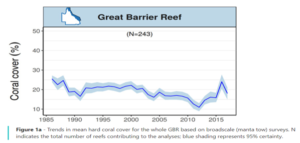

However, up 2016, AIMS did publish the average for the Great Barrier Reef (see for example the report for 2016/17 found at the above link) as shown in figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Screen-shot of the coral cover for the entire GBR from the AIMS website.

To produce the GBR average data from 1986 to 2022 (Figure 1) Ridd has used the graph published by AIMS (figure 2) for 1986 until 2017, and from 2017/8 to 2022, the sector data (as shown in Table 1 for 2022) is averaged (see Table 2).

| Sector | 2017/18 | 2018/19 | 2019/20 | 2020/21 | 2021/22 |

| Cape Grenville | 23.8 | 26.4 | 29.2 | 34.6 | 47 |

| PCB | 20.4 | 20.5 | 16.3 | 26.9 | 41 |

| Cooktown lizard | 9 | 10.2 | 12.8 | 21.4 | 25.3 |

| Cairns | 14.6 | 13.1 | 13.5 | 22.9 | 29.5 |

| Innisfail | 10.4 | 12.3 | 10.2 | 13.3 | 15.6 |

| Townsville | 19.4 | 18.8 | 19.6 | 26.6 | 34.7 |

| Cape Upstart | 24.2 | 24.2 | 24.2 | 25.8 | 30 |

| Whitsunday | 29.6 | 24.4 | 24.4 | 29.3 | 37.4 |

| Pompey | 20.2 | 18.5 | 25.1 | 33.4 | 31.8 |

| Swains | 29.7 | 20.4 | 24.2 | 25.4 | 21.8 |

| Cap Bunker | 39.4 | 49.1 | 44.5 | 52.6 | 58.6 |

| GBR Average assuming equal weight by sector | 21.9 | 21.6 | 22.2 | 28.4 | 33.9 |

| Northern Region

Grenville,PCB, Cooktown/Lizard |

17.7 | 19.0 | 19.4 | 27.6 | 37.8 |

| Central Region

Cairns to Whitsunday |

19.6 | 18.6 | 18.4 | 23.6 | 29.4 |

| Southern Region

Pompey Swains Cap Bunker |

29.8 | 29.3 | 31.3 | 37.1 | 37.4 |

Table 2: Summary of AIMS data since 2017/18. Yellow entries indicate sector not surveyed and result of previous survey has been used.

AIMS has effectively hidden the very good news about the Reef in 2022 by not publishing the GBR average data since 2017. This is because it is very unusual for all three major regions, and almost every sector, to be well above average at any moment in time. For example, the waves caused by a large cyclone will often kill large amounts of coral over a vast region, so some sectors are often recovering from such an event and have low coral cover. Only by seeing all the data aggregated as an average for the entire reef can the exceptional state of the coral cover be appreciated. AIMS shows graphs for all three major regions, and all have very high coral cover – but none are record breaking high. Because there is roughly a one in three chance that a region has very high coral cover, there is only a 1 in 27 chance that ALL three are high simultaneously. 2022 is exceptional because all three regions have very good coral cover at the same time.

It is surprising that AIMS no longer provides an average coral cover for the entre GBR because they have previously made far reaching claims about the poor state of the GBR based on data of GBR-wide average data. For example, when the coral cover hit a low point in 2011, after major cyclones destroyed large amounts of coral, AIMS authors (De’ath et al., 2012)[1] wrote in a very high-profile paper, that was widely quoted in the world media, the following:

Without significant changes to the rates of disturbance and coral growth, coral cover in the central and southern regions of the GBR is likely to decline to 5–10% by 2022. The future of the GBR therefore depends on decisive action. Although world governments continue to debate the need to cap greenhouse gas emissions, reducing the local and regional pressures is one way to strengthen the natural resilience of ecosystems (7, 9).

This prediction of 5-10% for 2022 has turned out to be incorrect as the average coral cover for all the regions is now over 30%. By no longer publishing the GBR average, it obscures the good data for 2022, and their inaccurate prediction of a decade ago.

Reason given for AIMS no longer providing GBR-average data

One reason, stated informally, seems to be that AIMS regards a single figure (the average) as not representative of the full diversity of the conditions on the reef. That is correct, but the average is nevertheless an interesting statistic, and the region, sector, reef and 140 m transect data is available for a more detailed discussion of the data.

AIMS is being inconsistent. It aggregates transect data to produce a single number for each surveyed reef. It aggregates reef data to produce a single number average for a sector. It aggregates reef/sector data to produce a single number average for each region – so why does it not aggregate reef/sector/region data to produce a single number average for the entire reef?

Nevertheless, AIMS should be congratulated for collecting such a remarkable data set over more than 3 decades. It is a huge data set, and Ridd estimates that AIMS has towed a diver roughly equivalent to around the world over this time.

Why is coral not 100% on a coral reef:

Coral cover is the percentage of the seafloor covered with coral. It is often assumed that coral cover should be 100% on a healthy coral reef. However, a reef is made of many different ecosystems. These include coral sand made from broken down coral, ancient dead coral ‘rock’, soft corals, algal beds, and crustose coralline algae which is a hard algae that helps cement together the dead coral on a coral reef. Dead coral is like concrete – it does not rot like wood. Coral grows on the dead bodies of their ancestors, and in doing so build ‘reefs”. Most of the reefs of the GBR have built up 50 to 100 meters above the surrounding seafloor in the last million years.

Final Comment:

The latest data on the GBR indicates it is in good shape. It happens to have a great deal of coral in 2022 because there have been few major mortality events over the last five to ten years. The three of four beaching events since 2016, which have been widely reported in the media, could not have killed much coral otherwise the 2022 statistics would not be so good.

The data since 1986 shows every region, every sector and most reefs have had periods of very low coral cover. This is entirely natural. Much is often made of this in the media. But a measure of the health of a system is the ability to recover from a major stress. Frail systems will not recover. Robust systems recover well. It is analogous to the ability of healthy people to recover well from inevitable diseases like covid19. Frail people are often killed by diseases. The GBR has proven to be a vibrant healthy ecosystem. This should not be a surprise; there is minimal people-pressure on the reef, and it is well protected. It is also unreasonable to expect that the small temperature rise over the last century (1oC) will have caused much impact, especially as it is well known that most corals grow faster in warmer water.

The data collected by AIMS shows that the GBR is a robust system with rapidly fluctuating coral cover. We must expect that, sometime in the future, a sequence of events will cause the coral cover to halve, as it did in 2011. We must then remember that this is almost certainly natural, and not allow the merchants of doom to depress the children.

[1] De’ath, G., Fabricius, K.E., Sweatman, H. and Puotinen, M. (2012). The 27-year decline of coral cover on the Great Barrier Reef and its causes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(44), pp.17995–17999.

For more on this topic see here and here.

Peter Ridd is a Member of the CO2 Coalition as well as a a geophysicist with over 100 publications, 35 years’ experience working on the Great Barrier Reef, and works on the physical oceanography of the reef, and also developed a wide range of world-first optical and electronic instruments for measuring environmental conditions near corals and other ecosystems.