Sunlight, the Bond Albedo, CO2, and Earth’s Temperature

R. Louw

Chemical Engineer, Stokesley, England

W. A. van Wijngaarden

Department of Physics and Astronomy, York University, Canada

W. Happer

Department of Physics, Princeton University, USA

November 27, 2025

Abstract

The main determinants of Earth’s absolute surface temperature, T, are the solar constant, S, the Bond albedo, A, and the effective emissivity for thermal radiation, ϵ. In this note we assume that the value of the effective emissivity, ϵ = ϵ(C), is determined by the atmospheric concentration C of CO2. We show that the solar constant is most important, the albedo is second, and the CO2 concentration is a distant third.

The surface-averaged heating flux, Zs, of the Earth by sunlight can be written as

Here

is the solar constant [1], the yearly averaged power passing through a square meter area that is normal to the direction of a ray from the center of the Sun to an observation point on Earth’s orbit. The solar constant is not really constant in time, and it varies by at least a few parts per thousand over a 11-year solar cycle. It is possible that there are larger, longerperiod variations of S that have not yet been characterized, but which have a signficant influence on climate.

Taking the radius of the Earth to be r, the factor of 1/4 of (1) comes from the ratio, 1/4 = πr2/4πr2 of the area πr2 of the circular cross section of the Earth that is illuminated by sunlight to the total surface area, 4πr2. The Bond albedo A of (1) is the fraction of solar radiation incident on the Earth that is reflected to space and not converted to heat by absorption in the atmosphere or surface [2]. The observed value of the Bond albedo is approximately

Contemporary small variations in the Bond albedo are mainly due to variations in cloud cover, and to a lesser extent, snow and ice cover.

The upward flux Zt of thermal radiation to space can be written as

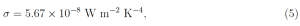

Here

is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant. We can think of (4) as the definition of the effective emissivity, ϵ. For a hypothetical, isothermal, black Earth, with no greenhouse gases, the effective emissivity would be ϵ = 1. For the real Earth the “local” effective emissivity for the local surface temperature is ϵ < 1 for most of Earth’s surface, mainly because the upward flux from the warm surface is replaced by weaker upward flux from greenhouse gases and clouds in the cold upper atmosphere. An exception is wintertime, cloud-free Antarctica, where there is normally a large temperature inversion. There, more radiation reaches outer space from CO2 and H2O emissions in the relatively warm upper atmosphere than is emitted at the same frequencies by the icy surface. So we often find ϵ > 1 for winter Antarctica.

In (4) we will take the average surface temperature of the Earth to be

In thermal equlibrium, the radiative cooling (4) of Earth by long-wave infrared radiation, will be equal to the solar heating (1) and we can write

An effective emissivity, averaged over the entire surface of the Earth, can be found by solving (7) with the values of S, A, σ and T from (2), (3), (5) and (6) to find

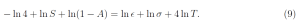

Taking natural logarithms of both sides of (7) we find

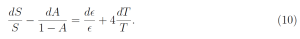

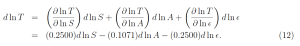

Suppose some change in the concentrations of greenhouse gases or cloud cover, or the solar constant causes the variables S, A, ϵ and T to change by small increments dS, dA, dϵ and dT . We assume that there is enough time after the changes to reestablish thermal equilibrium so (7) and (9) remain valid. Then we can take differentials of both sides of (9) to find

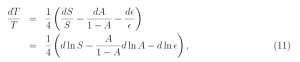

Solving (10) for the relative change in temperature we find

or

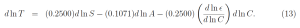

The numerical coefficient of d lnA in the bottom line of (12) comes from using the value A = 0.30 from (3) in (11). If we assume that the effective emissivity ϵ = ϵ(C) depends only on the CO2 concentration C, we can write (12) as

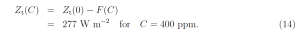

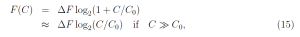

To find the factor d ln ϵ/d lnC of (13) we recall [3] that for clear skies in temperate latitudes the thermal flux (4) can be written in terms of a CO2 induced forcing F(C)

A simple empirical formula [3] that gives a good fit to the computer-calculated forcing of reference [4] is

where

and

From (4) and (14), and for C ≫ C0, we can write

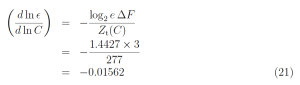

We differentiate the left side of (18) with respect to C, for constant T, to find

Differentiating the right side (18) in like manner, we find

Equating (19) and (20) we find

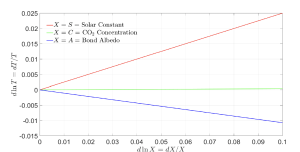

Figure 1: The relative changes d ln T = dT/T of Earth’s average, absolute surface temperature T caused by relative changes d ln S = dS/S, d lnC = dC/C and d lnA = dA/A of the solar constant S, the CO2 concentration C, and the Bond albedo A. Relative changes of CO2 have a much smaller effect on temperature than changes by the same relative amount of the solar constant S or the Bond albedo A.

Using (21) in (13) we find

From (22) we see that

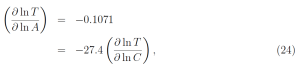

and

where the value of ∂ ln T/∂ lnC in the second line is given by (23). According to (24), a relative change d lnA = dA/A of the Bond albedo A causes a 27.4 times larger relative change (of opposite sign) in temperature d ln T = dT/T , than a relative change of the same magnitude, d lnC = dC/C, of the CO2 concentration C.

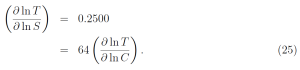

Eq. (22) also implies that

According to (25), a relative change d ln S = dS/S of the solar constant S causes a 64 times larger relative change of temperature d ln T = dT/T , than a relative change of the same magnitude, d lnC = dC/C, of the CO2 concentration C.

In summary, Fig. 1, (24) and (25) show that the most important influence on Earth’s surface temperature is the solar constant S, followed closely by the Bond albedo A. The CO2 concentration C has much less influence. For the same relative changes dC/C of the atmospheric CO2 concentrations, relative changes dS/S or dA/A cause relative warmings dT/T that are 64 and 27 times larger, respectively. As discussed in [3] and [4], this is because of the heavy saturation of the radiative forcing of CO2.

We have made many simplifying assumptions to keep this note as brief as possible. For example, we have characterized the Earth with a single characteristic temperature T or a single temperature change dT , as is commonly done for discusions of climate. Clouds probably diminish the clear-sky forcing changes due to changes in CO2 concentration, by about 30%. So the importances of the solar constant S and the albedo A relative to the CO2 concentration C are probably greater than indicated by (24) and (25), which were estimated for clear-sky conditions.

References

[1] The Solar Constant https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solar_constant

[2] The Bond Albedo https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bond_albedo

[3] Saturation Graphics, https://co2coalition.org/publications/saturation-graphics/

[4] W. A. van Wijngaarden and W. Happer, Dependence of Earth’s Thermal Radiation on Five Most Abundant Greenhouse Gases, Atmos. & Oceanic Phys., arXiv: 2006.03098 (2020).

Download the pdf here: Sunlight the Bond Albedo CO2 and Earths Temperature