05.5.2020

New Paper: Body condition of Barents Sea polar bears increased since 2004 despite sea ice loss

increased between 2004 and 2017 despite a pronounced decline in summer and winter sea ice extent.

“Unexpectedly, body condition of female polar bears from the Barents Sea has increased after 2005, although sea ice has retreated by ∼50% since the late 1990s in the area, and the length of the ice-free season has increased by over 20 weeks between 1979 and 2013. These changes are also accompanied by winter sea ice retreat that is especially pronounced in the Barents Sea compared to other Arctic areas” [Lippold et al. 2019:988]This result explains all the fat female polar bear photos coming out of the Svalbard region in recent years. However, it is totally at odds with predictions of catastrophic declines in polar bear numbers in the Barents Sea and assertions that Barents Sea bears are one of the most vulnerable to the effects of global warming (Amstrup et al. 2007; Hamiltion and Derocher 2019; Regehr et al. 2016; Stern and Laidre 2016) due to a dramatic loss of sea ice (see map below). And that is before the high levels of sea ice in the region I’ve been reporting on here, here, here, here, and here. Prior to this 2019 publication, all we have been provided with are body condition values for adult males (1993-2019) – showing them to have been doing well in recent years with no trend in body condition. Now, after years of loud public hand-wringing from polar bear activists, we find out that all along, adult females have been doing even better in recent years than they were before 2005 when there was more summer and winter ice. Therefore, contrary to expectations, Barents Sea and Chukchi Sea bears have been shown to be thriving with less sea ice – and for Barents Sea bears it’s a lot less ice.

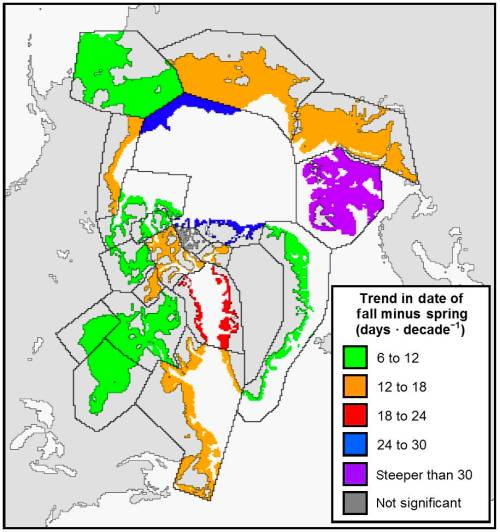

This map shows compares recent (1979-2014) declines in ‘summer’ sea ice extent (Stern and Laidre 2016, Fig. 12). Western and Southern Hudson Bay bears (green) are claimed to be doing poorly despite the smallest change in summer sea ice while Chukchi Sea bears are thriving under the same low ice loss; in contrast, Barents Sea bears are thriving (numbers increasing, body condition improving) despite living through the most dramatic summer ice declines in the Arctic (purple on the map). See also Regehr et al. 2016 and here.

“Body condition [of adult females], based on morphometric measurements, had a nonsignificant decreasing tendency between 1997 and 2005, and increased significantly between 2005 and 2017.“Later in the paper (pg. 988), they had this to say [my bold]:

“Unexpectedly, body condition of female polar bears from the Barents Sea has increased after 2005, although sea ice has retreated by ∼50% since the late 1990s in the area, and the length of the ice-free season has increased by over 20 weeks between 1979 and 2013. These changes are also accompanied by winter sea ice retreat that is especially pronounced in the Barents Sea compared to other Arctic areas. Despite the declining sea ice in the Barents Sea, polar bears are likely not lacking food as long as sea ice is present during their peak feeding period. Polar bears feed extensively from April to June when ringed seals have pups and are particularly vulnerable to predation, whereas the predation rate during the rest of the year is likely low.”Note this statement: “Despite the declining sea ice in the Barents Sea, polar bears are likely not lacking food as long as sea ice is present during their peak feeding period.” Martyn Obbard and colleagues (2016: 29) said essentially the same thing to explain why the body condition of Southern Hudson Bay polar bears had not declined in lock-step with sea ice declines in recent years. And I have said something very similar – many times – to explain why summer sea ice decline has not had a devastating effect on polar bears (Crockford 2017, 2019, 2020), a conclusion I arrived at from my review of the polar bear literature (including Obbard’s paper). Probably more than any other statement, it has been my insistence that summer sea ice is not essential polar bear habitat that I have been publicly disparaged and denigrated by journalists and colleagues (see also Harvey et al. 2018). It was undoubtedly also instrumental in the loss of my adjunct professor status. Yet it is what the evidence shows. Bottom line: Contrary to predictions, this new paper documents that the body condition of Barents Sea polar bears has improved significantly between 2005 and 2017 despite the most profound decline in summer sea ice of any polar bear subpopulation, which is consistent with a marked but non-statistically significant increase (42%) in population size (Aars 2018; Aars et al. 2017; Crockford 2017, 2019, 2020).